The Timeless Art of Grain Processing at Cable Mill

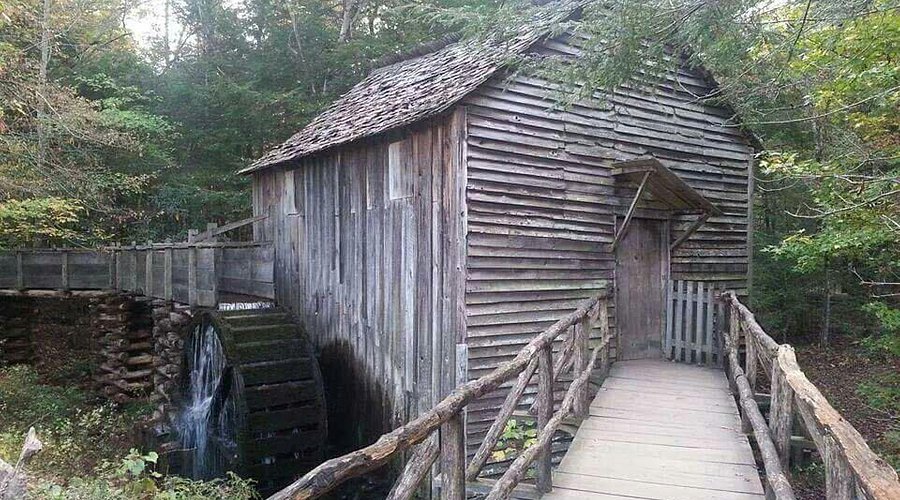

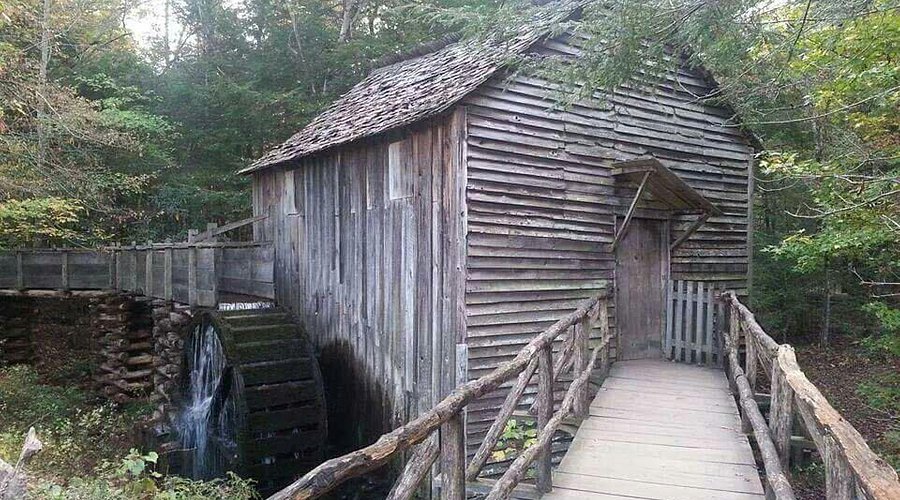

There’s something almost magical about watching a water-powered gristmill in action. The rhythmic turning of the wooden water wheel, the steady grinding of the millstones, and the scent of freshly ground grain fill the air with an energy that seems to echo the past. If you’ve ever wandered through Cades Cove, nestled deep in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, you’ve likely come across the historic gristmill known as Cable Mill—one of the last remaining links to the traditional grain milling practices that once sustained Appalachian communities.

Long before grocery store shelves were stocked with neatly packaged flour and cornmeal, early settlers relied on grain processing at Cable Mill and other water-powered mills to transform their harvests into essential ingredients for their daily meals. In those days, families grew their own corn and wheat, harvested it by hand, and brought it to the gristmill to be ground into meal and flour. It was an intricate, labor-intensive process, but one that was vital for survival. Cades Cove history is deeply tied to these traditional mills, which not only served as places of production but also as social and economic hubs where neighbors gathered, news was exchanged, and communities thrived.

Features

| Color | Brown |

| Size | 4 inch |

- Handmade in the USA

- Made of Birch Wood

- Ornament comes neatly packed and ready for gift giving

- 4 inches long

- Makes a perfect gift

Features

| Part Number | Illustrated |

| Release Date | 2011-08-15T00:00:01Z |

| Edition | Illustrated |

| Language | English |

| Number Of Pages | 128 |

| Publication Date | 2011-08-15T00:00:01Z |

- Used Book in Good Condition

Features

| Part Number | No Thorns Media |

| Color | Multi |

| Size | 4" |

- Adventure Awaits – Explore the World! Celebrate your love for travel with these stunning geography-themed adult stickers, perfect for travel stickers for luggage and scrapbooks, featuring iconic landmarks, breathtaking landscapes, and city skylines. Ideal for laptops, water bottles, cars, and more—take a piece of your favorite destination with you wherever you go!

- Built to Last – Weatherproof & Waterproof Stickers! Our premium vinyl stickers are made with high-quality materials to withstand rain, sun, and scratches. Designed with fade-resistant colors, they won’t crack or peel, ensuring long-lasting durability wherever you stick them!

- Bold Yet Compact – Designed for Ultimate Versatility! At 4 inches, these bumper stickers are the perfect size to stand out while fitting seamlessly on any surface. Whether it’s laptop stickers, water bottle stickers, car, tumbler, or skateboard, these cute stickers are made to complement your style!

- Easy to Apply & Remove – No Mess, No Fuss! Just peel & stick! The strong adhesive bond keeps your sticker secure, but when it’s time for a change, removal is a breeze—leaving no sticky residue behind.

- Explore More Unique & Fun Designs – Whether funny, aesthetic, or trendy, we’ve got something for everyone! From hilarious memes to stunning landscapes, adorable pets to action-packed sports themes. Discover more in our collection, available as stickers, magnets, mugs, tote bags, pin buttons, and patches. Mix, match, and collect!

A Journey from Seed to Flour

The story of grain processing at Cable Mill is one of resourcefulness and craftsmanship. Unlike modern flour production, which relies on industrialized processes, the Cable Mill represents a time when food production was local, sustainable, and deeply connected to the land. Here, water power—harnessed from Mill Creek—set a large wooden wheel into motion, transferring energy to massive millstones that crushed, ground, and sifted the grain. This process is a testament to the ingenuity of Appalachian settlers, who perfected these methods over generations.

But beyond its function, Cable Mill is a living piece of history—one that still operates today as a part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can witness the same grinding techniques used in the 19th century, seeing firsthand how raw grains were transformed into the cornmeal that would later become staples like cornbread, grits, and biscuits. This traditional grain milling process remains a fascinating example of early American technology, demonstrating how settlers maximized the natural resources around them to sustain their families.

The Legacy of Appalachian Milling

Mills like the one built by John P. Cable weren’t just tools for processing grain—they were essential to Appalachian culture and economy. Appalachian milling was a practice passed down through generations, each miller honing their craft and adjusting techniques to accommodate the specific grain grown in the region. The Cable Mill was one of many water-powered mills that dotted the Smoky Mountain landscape, but unlike most of its counterparts, it has been carefully preserved, allowing modern-day visitors to experience a key aspect of Cades Cove history.

In the early 1900s, as industrialization took hold and mass-produced flour and meal became more widely available, many of these mills fell into disrepair or disappeared entirely. However, thanks to the efforts of historians, conservationists, and the National Park Service, preserving Cable Mill has become a priority, ensuring that future generations can appreciate and learn from this remarkable example of historic gristmills. The mill continues to grind grain just as it did over a century ago, keeping this slice of history alive.

Why Grain Processing at Cable Mill Matters Today

In a world where convenience often takes precedence over tradition, understanding the grain processing at Cable Mill offers a refreshing perspective. It reminds us of a time when food production was deeply personal—when people knew where their food came from and took part in the process. This historic gristmill showcases a sustainable and efficient method of food production that relied entirely on renewable energy, something that modern sustainability advocates can appreciate.

Visiting the Cable Mill is more than just a walk through history—it’s a chance to see how innovation, necessity, and nature worked together to sustain communities. As you watch the water wheel turn and hear the grinding of the millstones, you can almost imagine the farmers who once stood in the same spot, waiting patiently for their grain to be transformed into the flour that would feed their families.

The Agricultural Roots: Growing and Harvesting the Grains

Before grain could be milled at Cable Mill, it had to be grown, harvested, and prepared—a process deeply intertwined with the rhythms of Appalachian life. Long before the days of grocery stores and mass-produced flour, early settlers relied on their own labor and expertise to cultivate the crops that sustained their families. Grain processing at Cable Mill didn’t begin at the millstones; it started in the fields, where farmers worked the land with tools, sweat, and a knowledge of the seasons passed down through generations.

The Appalachian Climate and Ideal Crops

The rugged yet fertile land of Cades Cove provided ideal conditions for grain cultivation. With its rich soil and moderate rainfall, the cove was a prime location for growing corn, wheat, and rye—staple grains that would later be processed at the historic gristmills dotting the landscape. Corn, in particular, thrived in the Smoky Mountains due to its adaptability to the region’s varying elevations and shorter growing seasons.

Unlike modern industrial farms that rely on pesticides and artificial irrigation, Appalachian milling traditions were built on sustainable agricultural practices. Farmers rotated their crops, allowing the soil to replenish its nutrients naturally. Many used companion planting techniques, growing beans alongside their corn to enrich the soil with nitrogen. These time-tested methods not only ensured successful harvests but also aligned with the self-sufficient lifestyle that defined Cades Cove history.

Traditional Farming Techniques

Farming in the 19th century was an arduous task, requiring long hours of labor and an intimate understanding of the land. Without modern machinery, Appalachian farmers relied on hand tools like scythes and sickles to harvest their crops. Fields were cleared by horse-drawn plows, and grain was gathered manually, a process that could take days or even weeks depending on the size of the harvest.

One of the most iconic farming practices of the time was shocking grain—a method in which wheat or rye was bundled and stood upright in the field to dry before being transported to the mill. This traditional grain drying process prevented mold growth and made it easier to separate the kernels from the stalk. Preserving these traditional grain milling techniques was crucial to ensuring a steady food supply, particularly in the isolated communities of the Smokies where store-bought goods were scarce.

For corn, another essential step in grain processing at Cable Mill was shelling. Once dried, the ears of corn were stripped of their kernels, often by hand or using a simple hand-cranked corn sheller. These kernels would then be taken to the gristmill, where they would be transformed into cornmeal—a staple ingredient in everything from cornbread to hominy.

Community Efforts in Planting and Harvesting

While we often picture early Appalachian settlers as fiercely independent, farming was rarely a solo endeavor. The process of growing and harvesting grain was a community effort, with neighbors banding together to help each other during peak seasons. It wasn’t uncommon for families to share farming equipment or gather in groups to assist with tasks like harvesting wheat or shucking corn.

Harvest time was also a period of celebration. Many communities held harvest festivals, where families came together to share food, play music, and give thanks for a successful growing season. These gatherings reinforced the bonds between neighbors and highlighted the cultural traditions that defined Cades Cove history.

The importance of Appalachian milling went beyond simple sustenance—it was a way of life. The farmers who brought their grains to Cable Mill weren’t just feeding their families; they were sustaining a tradition that had been in place for generations. Even today, visitors to historic gristmills like Cable Mill can catch a glimpse of the hard work and craftsmanship that went into producing the grains that shaped Appalachian cuisine.

Preparing the Grains for Milling

Once the harvest was complete, farmers had to carefully prepare their grain before taking it to the gristmill. Corn and wheat were stored in wooden granaries or corn cribs, which protected them from moisture and pests. These storage structures were designed with ventilated slats, allowing air to circulate and prevent spoilage—a simple yet effective engineering technique that has stood the test of time.

Some farmers even aged their grain, believing that a longer drying period resulted in a finer, more flavorful flour. The practice of aging grain before milling was common in many parts of Appalachia, with older generations swearing by the difference in texture and taste. This attention to detail is just one example of the wisdom embedded in traditional grain milling methods.

As the grains dried, families would plan their trips to Cable Mill—a journey that, for some, meant traveling several miles by foot or horse-drawn wagon. The anticipation of fresh-ground flour and cornmeal was enough to make the effort worthwhile. It was at this moment, as they loaded their grains for the trip, that farmers could finally see the fruits of their labor.

The process of grain processing at Cable Mill began long before the first kernel hit the grinding stones. From the careful selection of crops suited to the Smoky Mountain climate to the labor-intensive methods of planting and harvesting, every step was carried out with care and precision. Cades Cove history is deeply rooted in these agricultural traditions, and thanks to the preservation of sites like Cable Mill, we can still witness the journey from seed to flour as it was done centuries ago.

Next time you visit the historic gristmills of the Smokies, take a moment to appreciate the work that went into every bag of flour or cornmeal. The farmers who toiled in the fields, the families who gathered for harvest, and the millers who perfected their craft all played a role in keeping these traditions alive. And while technology has certainly advanced, there’s something undeniably special about the Appalachian milling techniques that continue to grind away at Cable Mill—powered not just by water, but by history itself.

Preparing the Grains for Milling

Once the fields of Cades Cove had yielded their bounty, the next crucial step in grain processing at Cable Mill was preparing the grains for the grinding process. This phase required patience and skill, ensuring that the harvested corn and wheat were properly dried, stored, and transported to the historic gristmills that played a vital role in Appalachian milling. Before a single kernel could meet the millstones, farmers had to take great care in preserving their crops—a process that was as much a part of Cades Cove history as the milling itself.

Drying and Storing the Harvest

Long before modern silos and industrial grain dryers, Appalachian farmers relied on natural methods to dry their harvest. Corn was often left in the fields to dry naturally on the stalk before being harvested, while wheat and rye were bundled into shocks and set upright to allow the sun and wind to complete the drying process. These traditional grain drying techniques ensured that moisture levels were low enough to prevent spoilage and produce high-quality flour and meal at the traditional grain milling sites like Cable Mill.

Once harvested, corn was stored in wooden cribs—ingeniously designed structures with slatted sides that allowed for air circulation while keeping pests at bay. These cribs could be found on nearly every farm in Cades Cove history, serving as a testament to the settlers’ understanding of grain preservation. Wheat, on the other hand, was often stored in barns or granaries until it was time to winnow, a process that separated the edible kernels from the chaff.

Proper storage was essential to ensure that the grain remained fresh until it could be milled. Farmers understood that excess moisture could lead to mold and spoilage, which would ruin the harvest. It was a delicate balance—too much humidity, and the grain would rot; too little, and it could become brittle and difficult to mill. Through trial and error, generations of Appalachian farmers perfected the art of grain storage, an often-overlooked but crucial step in grain processing at Cable Mill.

Transportation to the Mill

After the drying and storage process, it was time to transport the grain to Cable Mill, a journey that was often an event in itself. Unlike today, where a quick drive to the store provides easy access to flour and cornmeal, early settlers had to plan their trips to the mill carefully. Some farmers lived within walking distance, while others had to travel miles with their loaded wagons, carefully navigating the winding dirt roads of the Smoky Mountains.

For many, a trip to the historic gristmills wasn’t just about getting grain milled—it was a social occasion. Families and neighbors would often plan their visits together, turning what could have been a tedious chore into a chance to catch up on local news, share stories, and even barter goods. These visits were a vital part of Cades Cove history, reinforcing the close-knit nature of the community.

Farmers typically transported their grain in burlap sacks or wooden barrels, carefully packed to prevent spillage. The weight of these loads could be considerable, particularly for those bringing large harvests. Horses, oxen, and mules were commonly used to haul these goods, their slow but steady pace ensuring that the grain reached Cable Mill in prime condition.

One fascinating aspect of Appalachian milling was the reliance on natural resources for transport. Many farmers built hand-hewn wooden sleds, which were easier to maneuver on the rough terrain of the Smokies. These sleds, pulled by a single horse or mule, were often preferred over wagons during the wetter months when dirt roads turned to thick, impassable mud. The ingenuity of these methods further highlights the adaptability and resilience of those who depended on traditional grain milling.

The Anticipation of Freshly Milled Flour and Meal

For Appalachian families, the promise of freshly milled flour and cornmeal was worth every mile traveled to Cable Mill. Unlike the mass-produced, bleached flours found in modern supermarkets, the grains processed at historic gristmills like this one retained their natural nutrients, resulting in a richer, more flavorful product. Cornmeal ground at the mill had a coarse, hearty texture perfect for traditional Appalachian dishes like cornbread, grits, and Johnny cakes.

As they arrived at the mill, farmers would unload their grain, chatting with the miller and watching the rhythmic motion of the massive water wheel. The anticipation built as they waited their turn, the sound of grinding millstones filling the air. The moment when they received their sacks of freshly milled flour or meal was always satisfying—this was the food that would sustain their families through the coming months.

In some cases, the miller would take a milling fee, or toll, as payment for his services. Instead of charging cash, he would keep a small percentage of the grain he milled—usually about one-eighth of the total load. This barter system ensured that even those with little money could afford to have their grain processed, a testament to the community-oriented spirit of Cades Cove history.

The Connection Between Grain Processing and Self-Sufficiency

One of the most remarkable aspects of grain processing at Cable Mill was how it fit into the larger picture of Appalachian self-sufficiency. Unlike today, where flour and meal are commodities mass-produced in factories, 19th-century settlers had a direct hand in every step of food production. From planting the seeds to harvesting, drying, storing, and milling, they controlled their food supply in a way that few people today can imagine.

This process fostered a deep respect for the land and its resources. Every kernel of corn and grain of wheat represented hard work, patience, and an understanding of nature’s rhythms. Losing a crop to poor storage, pests, or a harsh winter could mean hardship for an entire family. That’s why the careful preparation and transport of grain to Cable Mill was taken so seriously—it was about survival, not just convenience.

Today, visitors to Cable Mill can still experience a slice of this history, watching as grains are ground just as they were over a century ago. This connection between past and present is what makes historic gristmills like this one so important to preserve. They offer us a rare glimpse into a world where food production was local, communal, and deeply tied to the land.

The journey from field to flour was never a simple one, but for the settlers of Cades Cove, it was a way of life. The grain processing at Cable Mill was the final step in a long, careful process that began with planting and harvesting and ended with the simple pleasure of fresh, stone-ground meal. Whether carried in burlap sacks, transported by horse-drawn wagon, or shared among neighbors, these grains represented far more than food—they symbolized tradition, self-reliance, and community.

By visiting Cable Mill today, we honor that legacy and keep the traditions of Appalachian milling alive. As you stand by the water wheel and listen to the steady churn of the grinding stones, take a moment to appreciate the generations of farmers and millers who made this place a cornerstone of Cades Cove history. Their dedication to traditional grain milling not only fed families but also wove the fabric of a community that endures in spirit to this day.

Looking Ahead: Exploring the Process from Seed to Flour

In this article, we’ll take you through every step of the grain processing at Cable Mill, from the early stages of planting and harvesting to the intricate workings of the gristmill itself. We’ll uncover how the milling process has evolved, explore the significance of mills in Appalachian history, and highlight ongoing efforts to preserve these fascinating pieces of the past.

So, step back in time with us, and let’s follow the journey from seed to flour, uncovering the remarkable history and craftsmanship behind one of Cades Cove’s most treasured landmarks. Whether you’re a history buff, a food enthusiast, or simply someone who appreciates a good old-fashioned story of hard work and ingenuity, this is a journey you won’t want to miss!

Inside the Cable Mill: The Mechanics of Grain Processing

The journey of grain processing at Cable Mill didn’t end when farmers dropped off their sacks of corn or wheat. Instead, it entered the heart of the operation—the grinding room, where the real magic happened. Powered by nothing more than the force of flowing water, historic gristmills like the Cable Mill were a marvel of engineering for their time. Unlike the automated machines of today, these mills relied on precision craftsmanship, careful adjustments, and the experience of the miller to transform raw grain into usable flour and meal.

Stepping inside the Cable Mill, you’re greeted by the rhythmic clatter of wooden gears, the scent of freshly ground grain, and the steady motion of massive millstones—each piece working together in a delicate but powerful system. Let’s take a closer look at the fascinating mechanics of this traditional grain milling process and how it shaped Cades Cove history.

How a Water-Powered Mill Works

Unlike modern roller mills, which use electricity and steel rollers to crush grain, the grain processing at Cable Mill follows an age-old method: stone grinding powered by water. This process begins outside the mill, where Mill Creek provides the energy needed to turn the heavy machinery inside.

Water is diverted from the creek through a wooden flume, a trough-like channel that directs the flow toward a large wooden water wheel. As the water spills over the wheel, its weight and movement turn the wheel’s axle, which extends into the mill and connects to a system of gears and pulleys. These mechanical components convert the vertical motion of the wheel into the horizontal power needed to spin the millstones.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Appalachian milling was how efficiently these mills operated. A well-maintained mill could grind up to 1,000 pounds of grain per day, all without electricity or complex machinery. This self-sustaining design made historic gristmills like the Cable Mill essential to rural communities, allowing farmers to process their crops locally rather than traveling long distances to more industrialized mills.

The Role of the Millstones: Precision in Action

At the heart of the traditional grain milling process are the millstones, massive circular stones that work together to grind grain into flour or meal. The Cable Mill uses a two-millstone system:

- The Bedstone (Bottom Stone): Fixed in place, serving as the stable surface.

- The Runner Stone (Top Stone): Rotates, creating friction that crushes the grain.

The gap between these stones is carefully adjusted by the miller, allowing for different grind textures. A finer grind was preferred for flour, while a coarser grind was ideal for cornmeal and animal feed. This level of customization ensured that the grain processing at Cable Mill could meet the needs of every farmer who brought in a harvest.

Another impressive feature of Appalachian milling was the artistry involved in maintaining these stones. The surfaces of the millstones needed to be regularly “dressed” or carved with intricate grooves that guided the grain outward as it was ground. If the stones became too smooth, they wouldn’t grind effectively. Skilled millers would use special chisels to re-cut these grooves—a laborious but necessary task to keep the mill operating at peak efficiency.

Fun fact: Some millstones used in historic gristmills were imported from Europe, made from a rare type of stone called French burr. However, many American mills—including the Cable Mill—relied on locally quarried stones, making them unique to their region.

The Mill’s Gear System: 19th-Century Engineering at Its Finest

Inside Cable Mill, an intricate system of gears, shafts, and pulleys work together to convert the water wheel’s energy into rotational force for the millstones. This was a mechanical masterpiece of early American ingenuity, built entirely from wood and iron.

One of the most fascinating components of the mill is the great spur wheel, a massive wooden gear that transfers power from the water wheel to the grinding mechanism. Attached to it are smaller lantern gears, which distribute energy to different parts of the mill, allowing for auxiliary functions like sifting flour or operating additional grinding stones.

The miller had to monitor this gear system closely, ensuring that everything was properly aligned and lubricated. If a gear broke or a shaft misaligned, the entire operation could come to a halt. Keeping a mill running required both technical know-how and constant maintenance, making the miller one of the most respected figures in Appalachian communities.

The Role of the Miller: A Skilled Trade

While grain processing at Cable Mill relied on mechanical systems, it was ultimately the miller’s expertise that determined the quality of the final product. Operating a historic gristmill wasn’t as simple as turning a wheel and letting the grain grind itself—every batch required careful monitoring.

Millers had to:

- Adjust the millstones to ensure the proper texture for flour or meal.

- Regulate the flow of grain to prevent clogging or overloading the stones.

- Listen for changes in sound, which could indicate a problem with the gears or stones.

- Test the final product to ensure consistency and quality.

A skilled miller could tell just by listening to the grinding stones whether the grain was feeding properly. If the mill made a low, steady hum, everything was running smoothly. If there was a high-pitched squeal or sudden silence, it meant something was wrong—and it needed to be fixed immediately.

One fascinating piece of Cades Cove history is that many millers passed down their trade from father to son, keeping these skills alive for generations. Unlike other trades, milling was both a science and an art, requiring a deep understanding of machinery, grain, and water flow.

A Step Back in Time: Experiencing the Mill Today

Today, visitors to Cable Mill can still witness this incredible process firsthand. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park Service operates seasonal demonstrations, allowing guests to see the traditional grain milling techniques in action. Watching the water wheel turn, hearing the grind of the stones, and feeling the coarse texture of freshly ground cornmeal brings history to life in a way no textbook ever could.

For those who want to take a piece of history home, the cornmeal ground at Cable Mill is often available for purchase, providing a tangible connection to Appalachian milling traditions that have stood the test of time.

The grain processing at Cable Mill is a remarkable example of historic gristmills at their finest—combining natural energy, mechanical ingenuity, and human expertise to create something as simple yet essential as flour and meal. Every step, from the turning of the water wheel to the careful adjustments of the millstones, speaks to the resourcefulness and craftsmanship of early Appalachian settlers.

Today, thanks to preservation efforts, we can still experience this slice of Cades Cove history, gaining a newfound appreciation for the hard work that went into something as simple as a loaf of bread or a pan of cornbread. Whether you’re a history buff, a mechanical enthusiast, or just someone who loves a good story of ingenuity, Cable Mill remains one of the best places to witness traditional grain milling in action.

So next time you’re in Cades Cove, take a moment to step inside the Cable Mill and listen to the echoes of the past—it’s a sound that has been grinding away for generations.

Features

| Color | Brown |

| Size | 4 inch |

- Handmade in the USA

- Made of Birch Wood

- Ornament comes neatly packed and ready for gift giving

- 4 inches long

- Makes a perfect gift

Features

| Part Number | Illustrated |

| Release Date | 2011-08-15T00:00:01Z |

| Edition | Illustrated |

| Language | English |

| Number Of Pages | 128 |

| Publication Date | 2011-08-15T00:00:01Z |

- Used Book in Good Condition

Features

| Part Number | No Thorns Media |

| Color | Multi |

| Size | 4" |

- Adventure Awaits – Explore the World! Celebrate your love for travel with these stunning geography-themed adult stickers, perfect for travel stickers for luggage and scrapbooks, featuring iconic landmarks, breathtaking landscapes, and city skylines. Ideal for laptops, water bottles, cars, and more—take a piece of your favorite destination with you wherever you go!

- Built to Last – Weatherproof & Waterproof Stickers! Our premium vinyl stickers are made with high-quality materials to withstand rain, sun, and scratches. Designed with fade-resistant colors, they won’t crack or peel, ensuring long-lasting durability wherever you stick them!

- Bold Yet Compact – Designed for Ultimate Versatility! At 4 inches, these bumper stickers are the perfect size to stand out while fitting seamlessly on any surface. Whether it’s laptop stickers, water bottle stickers, car, tumbler, or skateboard, these cute stickers are made to complement your style!

- Easy to Apply & Remove – No Mess, No Fuss! Just peel & stick! The strong adhesive bond keeps your sticker secure, but when it’s time for a change, removal is a breeze—leaving no sticky residue behind.

- Explore More Unique & Fun Designs – Whether funny, aesthetic, or trendy, we’ve got something for everyone! From hilarious memes to stunning landscapes, adorable pets to action-packed sports themes. Discover more in our collection, available as stickers, magnets, mugs, tote bags, pin buttons, and patches. Mix, match, and collect!

The Role of the Miller: Skill and Precision

The rhythmic hum of the millstones, the scent of freshly ground grain in the air, and the careful oversight of an experienced hand—this was the daily reality of the miller at Cable Mill. While the massive water wheel and intricate wooden gears performed the heavy lifting, it was ultimately the skill and precision of the miller that ensured grain processing at Cable Mill produced the high-quality flour and cornmeal that Appalachian families relied upon.

Operating a historic gristmill was no small task. The miller was responsible for monitoring every stage of the process, from adjusting the grind for different types of grain to maintaining the equipment that kept the operation running smoothly. Appalachian milling was both a science and an art, and the best millers knew how to listen, feel, and even smell their way to the perfect grind.

A Day in the Life of a 19th-Century Miller

For a working miller in Cades Cove history, the day often started before dawn. Farmers would arrive early, sometimes traveling miles with wagons loaded down with sacks of grain, hoping to have their harvest milled into usable flour or meal. The miller, already familiar with the community, might greet them by name, knowing exactly how they preferred their grain to be ground.

The first step in traditional grain milling was setting up the grind. The miller had to assess the condition of the millstones, ensuring they were properly aligned and sharp enough to process the grain efficiently. If the stones had worn smooth, they would need to be “dressed” or re-grooved—a painstaking process done by hand using chisels and hammers. A well-maintained set of millstones could last for decades, but only if they were carefully tended to by an experienced miller.

Once the water wheel was engaged and the machinery was running, the real work began. The miller had to carefully regulate the flow of grain into the millstones, ensuring that it neither poured too quickly—resulting in uneven grinding—nor too slowly, which could cause friction and overheating. Appalachian milling relied on experience; a good miller could tell just by the sound of the stones whether the grind was correct.

Listening to the Stones—The Miller’s Art

While modern flour production is automated with precise controls, grain processing at Cable Mill required a deep understanding of mechanics, physics, and even acoustics. The best millers didn’t need to check dials or gauges—they simply listened.

- A steady, low hum meant the stones were properly aligned and turning at the right speed.

- A high-pitched whine indicated the mill was running too fast and could damage the grain.

- A dull, thudding sound suggested the stones were out of balance and needed adjustment.

Experienced millers also used their hands to feel the flour or cornmeal as it emerged from the chute. The texture had to be just right—too coarse, and it wouldn’t be useful for baking; too fine, and it could clog the machinery. Historic gristmills like Cable Mill depended on the skill of the miller to get this balance just right.

The Toll System – Payment for Milling

Unlike today’s cash-based economy, payment at Cable Mill was often done through the toll system, a practice deeply rooted in Cades Cove history. Instead of charging farmers money for milling their grain, the miller would keep a percentage—usually one-eighth to one-tenth—of the finished product as compensation. This arrangement worked well in the barter-based economy of the Appalachian region, where cash was scarce, but goods were plentiful.

For the miller, this meant his livelihood depended on the productivity of the farmers in the area. A poor harvest could result in fewer customers, while a successful growing season meant an abundance of grain to mill—and more profit in return. This also ensured that grain processing at Cable Mill was a community effort, with the miller directly invested in the well-being of local farmers.

The toll system also created a secondary economy. Millers would often sell or trade the surplus flour and meal they collected, further embedding themselves into the community’s daily life. Local bakers, general stores, and even livestock owners would purchase grain from the miller, keeping the economic cycle of the Smokies alive and thriving.

Challenges and Hazards of Milling

Being a miller wasn’t just a skilled trade—it could also be a dangerous one. While traditional grain milling may seem like a peaceful process, there were hidden risks involved.

- Dust Explosions – Fine flour dust is highly flammable. If too much accumulated in the air, even a small spark from friction between the millstones could ignite an explosion. To combat this, millers had to keep their workspaces meticulously clean.

- Machinery Accidents – The gears, belts, and pulleys that powered Appalachian milling were unforgiving. A misplaced hand or loose piece of clothing could easily get caught, leading to serious injuries.

- Overheating Millstones – If the stones ground against each other without enough grain between them, they could overheat and cause a fire. Skilled millers had to monitor this constantly, ensuring a steady grain flow to prevent friction.

Despite these risks, millers were highly respected members of their communities. They provided an essential service that kept families fed and local economies running. The fact that Cable Mill still stands today is a testament to the skill and perseverance of the men who once worked within its walls.

The Miller’s Role in Community Life

Beyond the technical aspects of milling, the miller was often a central figure in Appalachian communities. The mill was not just a place of business but also a gathering spot, where farmers exchanged news, bartered goods, and discussed local events. In many ways, historic gristmills like Cable Mill were the heart of small-town life, serving as both an economic hub and a social center.

Millers were also keepers of knowledge. Many knew age-old techniques for improving flour quality, storing grain, and preventing spoilage. They often acted as informal advisors, helping farmers troubleshoot agricultural issues or offering tips on how to get the best results from their grain.

Some millers even passed down family recipes, sharing secrets for making the best cornbread, biscuits, or grits. This exchange of knowledge helped preserve Appalachian food traditions, many of which continue to this day in Southern kitchens.

The role of the miller in grain processing at Cable Mill was far more than just operating the machinery. It required technical skill, patience, and a deep connection to the community. These were the craftsmen who transformed the hard work of local farmers into flour and meal, feeding families throughout Cades Cove history and beyond.

Today, visitors to Cable Mill can still witness this extraordinary trade in action, stepping back into a world where water-powered wheels and grinding stones were the backbone of daily life. As we preserve historic gristmills like this one, we also keep alive the knowledge, traditions, and community spirit that made them such an essential part of Appalachian culture.

So next time you bite into a piece of cornbread or a warm biscuit, remember the millers who once toiled over their craft, ensuring that every grain of corn and wheat was ground to perfection—one turn of the water wheel at a time.

From Grain to Table: Flour and Cornmeal in Appalachian Cooking

The beauty of grain processing at Cable Mill wasn’t just in the mechanics or the history—it was in the final product. The cornmeal and flour ground by the massive millstones weren’t just commodities; they were the foundation of Appalachian cooking, shaping the daily meals of families in Cades Cove history. Long before store-bought flour and mass-produced grains became the norm, communities relied on historic gristmills like Cable Mill to supply the essential ingredients that would feed generations.

Even today, visitors to Cable Mill can purchase stone-ground cornmeal, a taste of the past that connects them to a tradition that has existed for centuries. From cornbread to biscuits, these grains weren’t just food—they were a way of life.

Staple Foods of the Appalachian Region

If there’s one dish that represents Appalachian milling, it’s cornbread. Corn was the dominant grain in the Smoky Mountains, thriving in the rocky terrain where wheat struggled. Unlike wheat, which required more intensive labor to cultivate and process, corn could be easily grown, harvested, dried, and ground into meal at traditional grain milling sites like Cable Mill.

Cornmeal was the backbone of countless Appalachian dishes, including:

- Johnnycakes – A simple fried cornmeal cake, often eaten for breakfast.

- Grits – Coarsely ground corn cooked into a creamy, hearty dish.

- Corn pone – A rustic, dense cornmeal bread cooked in a skillet.

- Hush puppies – Deep-fried cornmeal dough, often served with fish.

While wheat flour was less common in the early years of Cades Cove history, it became more widely available as historic gristmills like Cable Mill provided an easier way to process it. With the introduction of wheat flour, biscuits, dumplings, and pies became more popular, bringing even more variety to Appalachian kitchens.

For many families, these foods weren’t just meals—they were traditions. Recipes were passed down through generations, often handwritten in notebooks or memorized by heart. The same cornbread recipe that a grandmother made in the late 1800s might still be served at family gatherings today, connecting the past with the present through the simple magic of stone-ground grain.

The Role of Grain in Appalachian Self-Sufficiency

In the 19th century, settlers in Cades Cove didn’t have the luxury of frequent trips to a general store. Instead, they relied on grain processing at Cable Mill to turn their harvest into a long-lasting, versatile food source. Flour and cornmeal could be stored for months, ensuring that families had food even during harsh winters when fresh crops were unavailable.

This self-sufficiency was key to survival. A well-stocked pantry filled with stone-ground meal meant that a family could bake bread, make porridge, and prepare hearty meals even when fresh ingredients were scarce. Unlike modern refined flours, which lose much of their nutritional value during processing, the stone-ground grains from traditional grain milling retained essential oils and nutrients, making them healthier and more flavorful.

Many families also grew their own vegetables and raised livestock, supplementing their grains with fresh produce, dairy, and meat. But at the center of it all was the mill—historic gristmills like Cable Mill played an essential role in ensuring that no grain went to waste.

Traditional Cooking Techniques and Recipes

Cooking with stone-ground flour and cornmeal required different techniques than today’s pre-packaged ingredients. Because freshly ground grain contains more natural oils, it behaves differently in recipes—often requiring more moisture and careful attention to texture.

Many Appalachian families cooked their cornbread in cast iron skillets, which helped achieve a crispy, golden crust. A typical Cades Cove cornbread recipe might have included:

- 2 cups of stone-ground cornmeal

- 1 cup of buttermilk

- 1 egg

- A pinch of salt

- A spoonful of lard or bacon grease for flavor

These simple ingredients, combined with time-honored techniques, resulted in a dense, flavorful bread that was perfect for sopping up gravy or crumbling into soup.

For those lucky enough to have wheat flour, flaky biscuits became another beloved tradition. Unlike modern biscuit recipes that rely on baking powder, early Appalachian biscuits were often leavened with sourdough starter or buttermilk, giving them a tangy flavor and a tender crumb.

Pies were also a cherished way to use freshly milled flour. Apple, blackberry, and pumpkin pies were common, made from whatever fruit was in season and sweetened with sorghum or honey rather than refined sugar.

Cornmeal and Flour in Everyday Life

Beyond baking, grain processing at Cable Mill supplied ingredients that were used in surprising ways. Cornmeal, for example, wasn’t just for food—it was also used as a cleaning agent, helping to scrub cast iron skillets and wooden surfaces.

Cornmeal could even be used as animal feed, providing nourishment for livestock during the winter months. Farmers would often set aside a portion of their milled grain specifically for feeding chickens, pigs, and cows, ensuring that the entire household—both human and animal—benefited from the harvest.

Wheat flour, meanwhile, was sometimes reserved for special occasions. Since it was harder to come by than cornmeal, flour-based treats like cakes and pastries were often served only during holidays or celebrations. A fresh-baked apple stack cake, made from thin layers of molasses-sweetened dough and dried apples, was a traditional wedding dessert in the Smokies.

These culinary traditions were about more than just sustenance—they were part of the fabric of Appalachian life, woven into the community’s daily rituals, celebrations, and family gatherings.

Preserving Traditional Appalachian Cooking Today

Though the days of relying solely on historic gristmills for flour and meal are long gone, the traditions of Appalachian milling live on. Many modern homesteaders and heritage cooks are rediscovering the benefits of stone-ground grains, turning to mills like Cable Mill for high-quality, locally milled products.

Restaurants in Gatlinburg and surrounding areas also embrace these traditional ingredients, serving up classic Appalachian dishes made with heirloom cornmeal and flour. Whether it’s a slice of skillet cornbread at a country diner or a stack of biscuits smothered in sawmill gravy, the flavors of Cades Cove history continue to thrive.

For those looking to bring a taste of history home, Cable Mill often sells fresh-ground cornmeal, allowing visitors to cook with the same wholesome ingredients that sustained early settlers. Cooking with stone-ground meal is a way to connect with the past, experiencing firsthand the craftsmanship and tradition that went into grain processing at Cable Mill.

The impact of grain processing at Cable Mill extends far beyond the milling room—it lives on in the kitchens and traditions of the Smoky Mountains. Every loaf of cornbread, every plate of biscuits, and every steaming bowl of grits is a reminder of the historic gristmills that once powered Appalachian communities.

From the labor-intensive farming practices that brought grains to the mill to the careful work of the millers who ground them into meal, the journey from field to table was a process steeped in tradition and necessity. And while modern grocery stores have replaced the need for local mills, the flavors and stories of traditional grain milling remain an essential part of Cades Cove history.

So next time you take a bite of cornbread or a warm biscuit, remember that you’re tasting history—one that started with the turning of a water wheel and the grinding of stones at Cable Mill.

The Preservation and Restoration of Cable Mill

The journey of grain processing at Cable Mill is not just a tale of history—it is an ongoing commitment to preserving one of the last working historic gristmills in the Smoky Mountains. Nestled in Cades Cove, this mill stands as a living testament to Appalachian resilience, craftsmanship, and tradition. Without the efforts of historians, park rangers, and conservationists, traditional grain milling at Cable Mill could have easily faded into obscurity. Instead, thanks to dedicated restoration and preservation initiatives, visitors today can still witness this remarkable process just as it was done over a century ago.

Preserving Appalachian milling techniques is no small feat. From restoring the wooden water wheel to maintaining the hand-carved millstones, keeping Cable Mill operational requires a careful balance between historical accuracy and modern conservation efforts. The National Park Service, local craftsmen, and volunteers work tirelessly to ensure that Cades Cove history remains alive and accessible for future generations.

Keeping History Alive – The Role of the National Park Service

When Cades Cove became part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the 1930s, many of its original structures—including Cable Mill—were at risk of being lost. The Park Service recognized the significance of these buildings and took on the responsibility of preserving them as part of the region’s cultural heritage.

One of the first major restoration efforts focused on stabilizing the mill’s foundation. Years of water erosion had weakened the structure, making it vulnerable to collapse. Conservationists reinforced the foundation using historically accurate materials, ensuring that the mill retained its authenticity while standing strong against the elements.

Maintaining the water wheel has been another critical task. Since the wheel is exposed to the elements year-round, it requires regular repairs to prevent wood rot and deterioration. Skilled woodworkers, often using Appalachian milling techniques passed down through generations, replace individual planks as needed, keeping the wheel turning smoothly.

In addition to physical restoration, the Park Service also works to educate visitors about the grain processing at Cable Mill, offering guided tours, live demonstrations, and interactive exhibits. These efforts help ensure that the knowledge of traditional grain milling isn’t just preserved in wood and stone but also in the minds of those who visit.

The Challenges of Restoration and Conservation

Restoring a historic gristmill like Cable Mill comes with a unique set of challenges. Unlike modern buildings, which can be repaired with standardized materials, Cades Cove history demands a careful approach that respects original construction techniques and materials.

One major hurdle is finding the right type of wood. Many of the timbers used in the original construction were harvested from old-growth forests, a resource that is no longer readily available. To maintain historical accuracy, restoration teams must carefully source locally milled timber that closely matches the original wood in durability and appearance.

Another challenge lies in maintaining the millstones. Over time, these massive stones wear down, losing the sharp grooves that are essential for efficient grinding. In the past, skilled artisans—known as millwrights—were responsible for the painstaking task of “dressing” the stones, carefully re-carving the grooves by hand. Today, very few people possess this skill, making it increasingly difficult to find craftsmen capable of maintaining traditional grain milling equipment.

Weather also plays a significant role in the ongoing conservation efforts. The humid climate of the Smokies means that wooden structures like Cable Mill are constantly at risk of mold, rot, and insect damage. Regular maintenance, including sealant treatments and careful inspections, is crucial to preventing decay.

Despite these challenges, the commitment to preserving grain processing at Cable Mill remains strong. Through careful planning, skilled craftsmanship, and community support, this historic landmark continues to stand as a fully functional representation of Appalachian milling heritage.

Interactive Experiences for Visitors

One of the most exciting aspects of Cable Mill’s preservation is that visitors don’t just get to see history—they get to experience it. Thanks to the efforts of the National Park Service, the mill still grinds grain seasonally, allowing visitors to witness traditional grain milling firsthand.

During live demonstrations, park rangers operate the water wheel, feed grain into the millstones, and explain the mechanics of historic gristmills. The sight of corn being transformed into coarse meal, the sound of grinding stone, and the feel of freshly ground flour offer a sensory-rich experience that brings history to life.

In addition to the mill itself, the surrounding buildings—including a blacksmith shop and a historic barn—offer deeper insight into Cades Cove history. Visitors can learn about blacksmithing, woodworking, and farming techniques, all of which were essential to the early settlers who depended on mills like this one for survival.

For those who want to take a piece of history home, freshly ground cornmeal is often available for purchase. This allows modern cooks to experience the flavor and texture of stone-ground meal, connecting them directly to the traditions of Appalachian milling.

Community Efforts and Volunteer Contributions

The preservation of Cable Mill isn’t just the work of historians and park rangers—it’s also a community-driven effort. Over the years, local craftsmen, volunteers, and history enthusiasts have played a vital role in keeping the mill operational.

Many of the restoration projects have been funded through grants and donations, with organizations dedicated to preserving Southern history contributing resources. Skilled tradespeople volunteer their time to help repair structures, ensuring that the work is done using historically accurate methods.

Educational groups also visit the mill, with students and researchers studying traditional grain milling as part of their coursework. These hands-on learning experiences help inspire a new generation of historians, engineers, and conservationists, ensuring that the knowledge of grain processing at Cable Mill continues to be passed down.

The Future of Cable Mill’s Preservation

Looking ahead, the future of Cable Mill will rely on a combination of traditional craftsmanship and modern technology. While the goal is to maintain historical accuracy, new advancements in digital documentation, 3D scanning, and material conservation can aid in keeping the mill in pristine condition.

For example, preservationists are now using 3D scanning technology to create digital blueprints of the mill’s structure. These scans allow restoration teams to identify weak points, plan repairs, and ensure that replacement parts are made to exact specifications.

Additionally, sustainable preservation techniques are being explored to reduce environmental impact. Using locally sourced timber, natural sealants, and eco-friendly maintenance practices ensures that the restoration process aligns with the principles of conservation that define the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

By continuing to invest in these preservation efforts, future generations will be able to experience the magic of grain processing at Cable Mill just as visitors do today.

Preserving grain processing at Cable Mill isn’t just about maintaining an old building—it’s about protecting a piece of living history. Thanks to the dedication of historians, conservationists, and local volunteers, this historic gristmill remains a functioning reminder of Appalachian ingenuity.

From the careful restoration of the water wheel to the seasonal milling demonstrations, Cable Mill is more than just a tourist attraction—it’s a bridge to the past. Every visitor who walks through its doors, watches the grinding stones in motion, or takes home a bag of freshly milled cornmeal becomes part of its ongoing story.

As long as there are people willing to learn, restore, and appreciate the art of Appalachian milling, the traditions of Cades Cove history will continue to thrive. So whether you’re a history buff, a lover of Southern food, or simply someone who values the past, a visit to Cable Mill is a chance to step back in time and witness history in motion—one turn of the water wheel at a time.

The Importance of Historical Mills in Today’s World

The grain processing at Cable Mill is more than just a glimpse into the past—it serves as a reminder of how communities once thrived on local resources, ingenuity, and sustainable practices. As modern food production becomes increasingly industrialized, the lessons we can learn from historic gristmills like Cable Mill have never been more relevant.

In today’s fast-paced world, where pre-packaged foods dominate grocery store shelves and mass production prioritizes efficiency over quality, stepping inside Cable Mill offers a striking contrast. It reminds us that traditional grain milling was once an art—one that emphasized freshness, craftsmanship, and a deep connection to the land. But beyond nostalgia, the continued operation of this historic mill provides insights into sustainability, self-sufficiency, and food security that are crucial even in modern times.

A Lesson in Sustainability

One of the most significant takeaways from grain processing at Cable Mill is the sustainable nature of Appalachian milling. Unlike modern flour mills, which rely on massive industrial machinery powered by fossil fuels, historic mills like this one used renewable energy—water power—to process grains.

This method of harnessing natural energy not only made historic gristmills self-sufficient but also left a minimal environmental footprint. By utilizing the steady flow of Mill Creek, Cable Mill operated without the need for electricity, burning fuels, or generating waste. In contrast, modern grain milling often involves large-scale monoculture farming, energy-intensive processing, and long transportation routes, all of which contribute to environmental degradation.

As conversations about sustainable agriculture and renewable energy grow louder, places like Cable Mill serve as valuable case studies in how communities once operated efficiently while working in harmony with nature. Visitors can witness firsthand how traditional grain milling relied on zero-emission energy sources, setting an example for the eco-conscious movements of today.

The Value of Locally Processed Foods

Before the rise of mass food production, families relied on local mills to process their grains. This not only ensured fresher, more nutritious flour and meal but also supported local economies. In the 19th century, Appalachian milling was a crucial part of community life, providing a centralized location where farmers could have their grain ground while exchanging news, goods, and services.

Fast forward to today, and many people are rediscovering the benefits of stone-ground grains, thanks to the growing popularity of farm-to-table movements and artisanal food production. Unlike the ultra-refined flours produced in modern industrial mills, stone-ground meal from historic gristmills like Cable Mill retains more natural oils, nutrients, and flavors, making it a healthier and tastier alternative.

With more people seeking organic, non-GMO, and locally sourced foods, the importance of small-scale grain milling is experiencing a revival. Millers across the country are once again using traditional grain milling techniques, inspired by places like Cable Mill, to create high-quality, heritage grain products that honor the past while serving the present.

Learning from the Past for a More Resilient Future

Beyond food production, grain processing at Cable Mill teaches valuable lessons about self-sufficiency and resilience. In an era where supply chain disruptions, food shortages, and environmental concerns are becoming more frequent, looking to the past can help us find solutions for the future.

Early settlers in Cades Cove history didn’t have supermarkets or global food distribution networks to rely on. Instead, they cultivated their own grains, processed them at historic gristmills, and stored their food for long-term survival. This self-reliance ensured that families could weather harsh winters, crop failures, or economic downturns without being entirely dependent on external sources.

In contrast, today’s food system is highly centralized and vulnerable to disruptions. The global pandemic, for example, exposed the fragility of supply chains, leading many to rethink the importance of local food systems. By studying Appalachian milling, we gain insight into how communities once operated in a way that was both sustainable and resilient, offering a blueprint for modern food security initiatives.

The Revival of Traditional Milling Techniques

While most modern grain production has moved to massive industrial operations, a growing number of farmers, bakers, and homesteaders are working to bring back traditional grain milling. Inspired by places like Cable Mill, these individuals are investing in small-scale stone mills to produce fresh, locally sourced flour and meal.

This movement isn’t just about nostalgia—it’s about quality and sustainability. Traditional stone-ground flour retains more flavor and nutrition compared to modern refined flour, making it a favorite among artisan bakers and chefs. Additionally, supporting local mills helps reduce the carbon footprint of food production, cutting down on transportation costs and energy consumption.

Several small mills in the Appalachian region have been restored and brought back into operation, offering fresh stone-ground meal to local communities. These efforts highlight how the knowledge and techniques preserved at Cable Mill continue to inspire new generations of millers, farmers, and food enthusiasts.

The Connection Between History and Culinary Heritage

For those who love history, grain processing at Cable Mill is more than just a mechanical process—it’s a connection to the culinary traditions that shaped Cades Cove history. The cornbread, biscuits, and grits that were once daily staples for Appalachian families are still enjoyed today, keeping these flavors alive across generations.

Many Southern chefs and home cooks are returning to traditional recipes, using stone-ground cornmeal and flour from historic gristmills to create authentic Appalachian dishes. Whether it’s a cast-iron skillet full of golden cornbread or a batch of flaky homemade biscuits, these foods remind us that history isn’t just something we read about—it’s something we can taste.

As food culture continues to evolve, preserving these culinary traditions ensures that future generations can experience the same rich flavors and time-honored techniques that defined early Appalachian life.

The Role of Historic Mills in Education and Tourism

Beyond their contributions to food and sustainability, historic gristmills like Cable Mill play an important role in heritage tourism and education. Every year, thousands of visitors come to Cades Cove to witness traditional grain milling in action, learning about the craftsmanship and history that made these mills essential to Appalachian communities.

For many, seeing the water wheel turn, hearing the grinding of the millstones, and feeling the texture of freshly ground meal offers a hands-on experience that brings history to life in a way that books and museums simply can’t. Educational programs and live demonstrations help visitors—especially children—understand the value of local food production, historical preservation, and sustainable practices.

With the rise of eco-tourism and heritage travel, sites like Cable Mill are becoming even more valuable as destinations where visitors can engage with living history. Supporting these mills through tourism, donations, and volunteer efforts ensures that they remain operational for future generations to enjoy and learn from.

The grain processing at Cable Mill isn’t just a relic of the past—it’s a timeless example of sustainability, craftsmanship, and community resilience. From its role in Appalachian milling to its contributions to Cades Cove history, this historic gristmill continues to provide valuable lessons for the modern world.

As interest in local food, traditional grain milling, and heritage tourism continues to grow, mills like Cable Mill serve as reminders that the past still has much to teach us. Whether you visit to witness a live milling demonstration, purchase fresh stone-ground meal, or simply admire the engineering of the water wheel, your experience contributes to keeping history alive.

In an era where convenience often overshadows tradition, places like Cable Mill remind us that the best things—whether it’s a bag of freshly ground cornmeal or the wisdom of generations past—are worth preserving.

Honoring the Legacy of Grain Processing at Cable Mill

As we’ve explored, the grain processing at Cable Mill is not merely a historical curiosity—it is a living testament to the ingenuity, resilience, and community spirit of the early Appalachian settlers. This historic gristmill, nestled in the heart of Cades Cove, continues to grind out stories as rich and textured as the cornmeal it produces. Its significance extends far beyond the mechanical processes of grinding grain; it represents a way of life that valued hard work, sustainability, and a deep connection to the land.

Visiting Cable Mill today is like stepping back in time. The turning of the water wheel, the hum of the grinding stones, and the scent of freshly milled grain evoke a simpler era when food production was local, sustainable, and essential to survival. This experience reminds us that the methods of traditional grain milling are not relics of the past but vital lessons for the present and future.

The Enduring Impact of Appalachian Milling

The legacy of Appalachian milling is evident not only in the preserved structures of Cable Mill but also in the cultural traditions it has inspired. The mill represents a critical chapter in Cades Cove history, a time when communities relied on one another to sustain their livelihoods. Farmers brought their harvests to the mill with the knowledge that their grain would be transformed into flour and meal that would nourish their families through the seasons.

This tradition of mutual support and local production is just as relevant today. As modern society grapples with questions of sustainability and food security, the practices of traditional grain milling provide valuable insights into how communities can thrive while minimizing their environmental impact.

A Window Into the Past

One of the most remarkable aspects of grain processing at Cable Mill is how it connects us to the past in a tangible way. Unlike static displays in a museum, the working mill offers a sensory-rich experience. You can hear the rhythmic grind of the stones, feel the texture of freshly ground cornmeal, and even take home a bag to use in your own kitchen.

This connection to the past is what makes historic gristmills like Cable Mill so special. They are not just buildings; they are living artifacts that tell the story of a people who thrived in harmony with the land. Through preservation efforts, this story continues to be told, inspiring visitors from all walks of life.

Lessons for Modern Times

The grain processing at Cable Mill also serves as a reminder of the value of slow, deliberate craftsmanship in an age dominated by speed and convenience. In today’s world, where highly processed foods and industrial agriculture have become the norm, the practices of Appalachian milling stand out as a model of sustainability and quality.

Stone-ground grains, like those produced at Cable Mill, retain more of their natural oils and nutrients, offering a healthier and more flavorful alternative to modern refined flours. By embracing these traditional methods, we not only honor the past but also make choices that benefit our health and the environment.

Preserving a Shared Heritage

The continued operation of Cable Mill is a testament to the dedication of historians, conservationists, and volunteers who recognize the importance of preserving Cades Cove history. Through restoration projects, educational programs, and interactive demonstrations, they ensure that future generations can experience the magic of traditional grain milling firsthand.

One visitor, reflecting on their trip to Cable Mill, said it best: “It’s not just a mill; it’s a reminder of how connected we once were to our food and to each other.” This sentiment captures the heart of why preserving historic gristmills like Cable Mill is so important.

A Call to Action

Preserving the legacy of grain processing at Cable Mill requires ongoing support from the community. Whether it’s through donations, volunteering, or simply visiting the mill and sharing its story, every effort helps to keep this piece of Cades Cove history alive.

As you explore the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, consider stopping by Cable Mill to witness the enduring beauty of Appalachian milling. Participate in a guided tour, watch the water wheel turn, and take home a bag of freshly ground meal as a souvenir of your journey through time.

A Living Legacy

The story of grain processing at Cable Mill is far from over. With each turn of the water wheel and every bag of cornmeal produced, the mill continues to serve as a bridge between the past and the present. It reminds us of the ingenuity and hard work of those who came before us, while also offering valuable lessons for how we can live more sustainably today.

As you leave the mill and walk through the fields of Cades Cove, take a moment to reflect on the countless hands that have touched this land—the farmers, millers, and families who built a life here. Their legacy lives on in the grinding stones of Cable Mill, ensuring that their stories will continue to be told for generations to come.

So, next time you find yourself in the Smoky Mountains, don’t just visit Cable Mill—experience it. Let the history, the craftsmanship, and the spirit of Appalachian milling inspire you, just as it has inspired countless others before. Because preserving the past isn’t just about looking back; it’s about moving forward with a deeper appreciation for the traditions that ground us.

Leave a Reply